wcag heading

From Pg. 12

Then Annie walked over to the bookcases lining her living room. After a few minutes she found what she was looking for. The bible her parents had given her, when she’d been baptized. For people who didn’t attend church, they still followed the rituals.

Louise’s Thoughts:

Armand and Reine-Marie are like many of their generation, and those who are younger. While not following any particular religion, they have a profound spiritual life and belief. But, somewhat contradictorily, they find the rituals meaningful and comforting. Church at the holidays. Baptisms, funerals, weddings in churches. Though the services themselves might be led by friends. The hymns. Many of the prayers are repeated by the Gamaches. Armand will cross himself, when faced with a body. These are hardwired into us. And offer comfort and some sense of continuity.

From Pg. 19

At the very end of the bay a fortress stood, like a rock cut. Its steeple rose as though propelled from the earth, the result of some seismic event. Off to the sides were wings. Or arms. Open in benediction, or invitation. A harbor. A safe embrace in the wilderness. A deception.

Louise’s Thoughts:

Again, this highlights the contradictions many modern Quebecois, and others, find in the trappings of religion. That a church, a monastery, a cathedral could offer both sanctuary and betrayal. That the monastery of St Gilbert, and its occupants, are both of this world, and expelled from it.

From Pg. 30

“All shall be well,” said Dom Philippe, looking directly at Gamache. “All shall be well; and all manner of thing shall be well.”

It wasn’t at all what the Chief had expected the abbot to say and it took him a moment, looking into those startling eyes, to respond.

“Merci. I believe that, mon père,” said Gamache at last. “But do you?”

Louise’s Thoughts:

I liked exploring, in more depth, Armand’s relationship with the institution of religion, and the teachings. His clear displays of respect for the abbot and the other monks, while being aware of recent (and perhaps not so recent) history. I also liked how the abbott could surprise Armand, by quoting a mystic. And a woman. And I liked that Armand recognized the quote as coming from Julian of Norwich. Not perhaps surprisingly, I have a bracelet with that quote, which I cherish. It was given to me by my editor, Hope Dellon, to celebrate the publication of THE BEAUTIFUL MYSTERY. It proved both the truth and a comfort for what was to come.

From Pg. 146

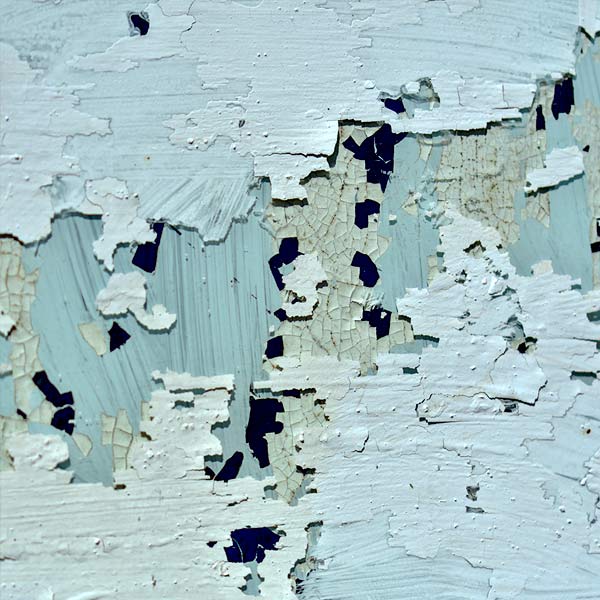

Gamache glanced through the leaded-glass window. It made the world outside look slightly distorted. But still he yearned to step into it. And stand in the sunshine. Away, even briefly, from this interior world of subtle glances and vague alliances. Of notes and veiled expressions.

Louise’s Thoughts:

Here Armand is feeling oppressed, closed in. The peace he had felt at first, is dissipating, as he discovers more and more about the interior life of the monastery and the monks. As he begins to see more clearly what is really happening, and decode what the music really means to them. It’s also an allusion to perception, and how it is affected by where we stand. From the inside of St Gilbert looking out, the world is warped. While to many on the outside, looking at the life of these monks, their monastic life is warped, unhealthy. Unnatural. It reminds me of a quote, one I believe I used in an earlier book. When Henry David Thoreau was arrested for civil disobedience (not paying a tax that went against his conscience), Emerson visited him in jail. Emerson asked Thoreau, “Henry, what are you doing in there?” Thoreau replied, “Waldo, the question is what are you doing out there?” Perception. Perspective. Choice.

From Pg. 52

For the first time, Gamache began to wonder if the garden existed on different planes. It was both a place of grass and earth and flowers. But also an allegory. For that most private place inside each one of them. For some it was a dark, locked room. For others, a garden.

Louise’s Thoughts:

Again, the theme repeated in many of the books but perhaps most profoundly in this one, of perspective. Of what is ‘inside’, what is ‘out’? Is the purpose of St Gilbert to keep the the devout monks safe from the sins of the outside world? Or the world safe from the monks? Is it a garden, or a wall? Safety or a prison? Is the music a gift from God to be shared? Or a direct line to a Higher Power, meant only for a chosen few? Again, it reminds me of a quote, this time a perhaps apocryphal headline from the London Times. The homes formed a circle, and in its center was the village green. And in the center of that were the pine trees that soared over the community. Three great spires that inspired the name. Three Pines. These were no ordinary trees. Planted centuries ago, they were a code. A signal to the war- weary.When reporting on a spectacularly dense mist, the headline read: Heavy Fog. Mainland Cut Off.