wcag heading

It strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room.

William Shakespeare (Epigraph, A Great Reckoning)

The Shakespeare quote comes from the comedic play, As You Like It (Act III, Scene III), and is believed to have been written in 1599. The line is a direct reference to Christopher Marlowe’s death which occurred six years earlier under extremely suspicious circumstances.

The Shakespeare quote comes from the comedic play, As You Like It (Act III, Scene III), and is believed to have been written in 1599. The line is a direct reference to Christopher Marlowe’s death which occurred six years earlier under extremely suspicious circumstances.

Marlowe, a mercurial figure in Elizabethan England, was a rumored spy, a possible heretic, a poet, and, above all, the greatest playwright of his era, up until his untimely death at the age of 29, when Shakespeare would assume the mantle.

The “reckoning” that led to Marlowe being stabbed to death was purportedly over an unpaid bill, although the man who wielded the dagger, Ingram Frizer, was—like Marlowe—linked to espionage and the motive for murder was perhaps more political than pound sterling based.

So great was Marlowe’s influence on the Bard that there are theories that Marlowe was indeed Shakespeare himself. For over 400 years, the question of “did Shakespeare actually pen the plays attributed to him?” has loomed large. Marlowe is but one of the possible candidates. Others include Francis Bacon, Edward de Vere, Sir Walter Raleigh, and—the most curious of all in my opinion—Amelia Bassano Lanyer.

Lanyer (1569-1645) was one of the first women in England to publish her own poetry and to operate her own school. She is also credited as a pioneer of the feminist movement. In short, Amelia Bassano Lanyer was smart, unique, and strong-willed.

Lanyer (1569-1645) was one of the first women in England to publish her own poetry and to operate her own school. She is also credited as a pioneer of the feminist movement. In short, Amelia Bassano Lanyer was smart, unique, and strong-willed.

Enter (Stage Left) Louise’s character, Amelia Choquet.

Amelia, as introduced in A Great Reckoning, is certainly unique, classically smart, and exceptionally strong-willed.

And, the name Amelia has a singular importance in Armand Gamache’s familial history.

“Armand Gamache sat in the little room and closed the dossier with care, squeezing it shut, trapping the words inside.”

And so begins the 12th novel in the Three Pines canon and, for those of you who have read it, you know that the book contains a major settling of accounts, a great reckoning, if you will.

For those of you who have read the 11th installment in the Louise Penny canon, you know that this retort, directed at Gamache, comes at a crucial moment in the plot. It’s the only time the phrase, the nature of the beast, is used within the novel but the power it conveys is so strong it titles the book. The Oxford Dictionary defines the expression as “The inherent and unchangeable character of something” and the phrase itself first appeared in John Ray’s Collection of English Proverbs which was published in the 1600’s.

For those of you who have read the 11th installment in the Louise Penny canon, you know that this retort, directed at Gamache, comes at a crucial moment in the plot. It’s the only time the phrase, the nature of the beast, is used within the novel but the power it conveys is so strong it titles the book. The Oxford Dictionary defines the expression as “The inherent and unchangeable character of something” and the phrase itself first appeared in John Ray’s Collection of English Proverbs which was published in the 1600’s. “Oui,” said Beauvoir, caution creeping into his voice.

“Oui,” said Beauvoir, caution creeping into his voice.

Though not the same as the 2004 book, Louise does acknowledge Robinson’s novel as “remarkable” and, in fact, two pages later in The Long Way Home Clara quotes directly from Robinson’s work, “I’ll pray that you grow up a brave man in a brave country. I will pray you find a way to be useful.”

Though not the same as the 2004 book, Louise does acknowledge Robinson’s novel as “remarkable” and, in fact, two pages later in The Long Way Home Clara quotes directly from Robinson’s work, “I’ll pray that you grow up a brave man in a brave country. I will pray you find a way to be useful.”

Louise goes on to tell us that she first used the words in her second book.

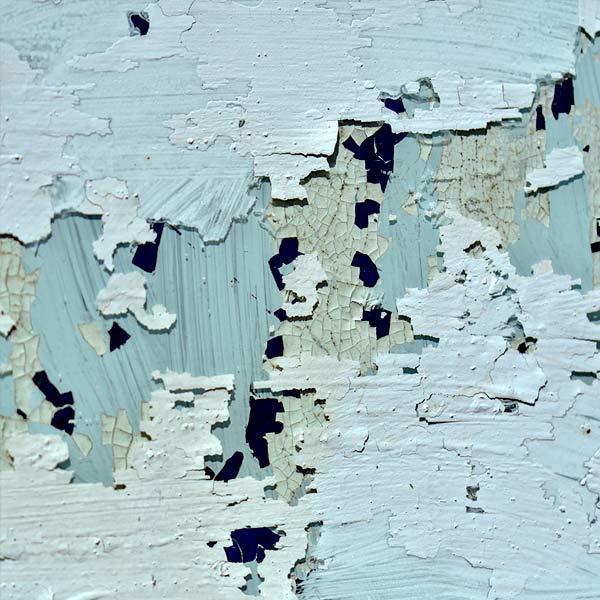

Louise goes on to tell us that she first used the words in her second book. That statement, to me, epitomizes Louise’s choice for the title and its connection to Leonard Cohen’s profound words. As Cohen said himself in a rare interview in the early 90’s, “And worse, there is a crack in everything that you can put together: Physical objects, mental objects, constructions of any kind. But that’s where the light gets in, and that’s where the resurrection is and that’s where the return, that’s where the repentance is. It is with the confrontation, with the brokenness of things.”

That statement, to me, epitomizes Louise’s choice for the title and its connection to Leonard Cohen’s profound words. As Cohen said himself in a rare interview in the early 90’s, “And worse, there is a crack in everything that you can put together: Physical objects, mental objects, constructions of any kind. But that’s where the light gets in, and that’s where the resurrection is and that’s where the return, that’s where the repentance is. It is with the confrontation, with the brokenness of things.”

Gamache’s quote above, as he points out, is a direct line from T.S. Eliot’s play, Murder in the Cathedral, and he repeats it in Louise’s eighth novel when confronted by an ominous plaque that may hold a clue to murder. Eliot’s play is a perfect reference as Gamache has come to the monastery of Saint-Gilbert-Entre-les-Loups to investigate a homicide.

Gamache’s quote above, as he points out, is a direct line from T.S. Eliot’s play, Murder in the Cathedral, and he repeats it in Louise’s eighth novel when confronted by an ominous plaque that may hold a clue to murder. Eliot’s play is a perfect reference as Gamache has come to the monastery of Saint-Gilbert-Entre-les-Loups to investigate a homicide. T.S. Eliot, who was also a big inspiration on

T.S. Eliot, who was also a big inspiration on

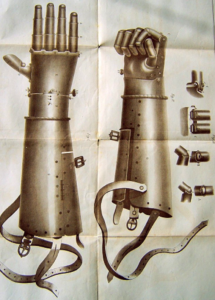

That “German guy” is none other than Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the quote originally appeared in 1773 in his play, “Götz von Berlichingen”. Goethe’s drama focused on the life of Gottfried von Berlichingen, a Knight who fought in the Crusades, lost his arm to cannon fire, and wore a prosthetic “Iron Fist” thereafter.

That “German guy” is none other than Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the quote originally appeared in 1773 in his play, “Götz von Berlichingen”. Goethe’s drama focused on the life of Gottfried von Berlichingen, a Knight who fought in the Crusades, lost his arm to cannon fire, and wore a prosthetic “Iron Fist” thereafter. Goethe uses Götz as a symbol of an individual with integrity—be it a free spirit, a rebel, an artist, etc.—trying to live within a dishonest society. Sure sounds a lot like our dear Chief Inspector Gamache, no?

Goethe uses Götz as a symbol of an individual with integrity—be it a free spirit, a rebel, an artist, etc.—trying to live within a dishonest society. Sure sounds a lot like our dear Chief Inspector Gamache, no?

The quote is indeed Horace and originates in his Odes (111.2.13) and as Dr. Croix, the archeologist, points out, essentially means, “It is sweet and right to die for your country.” To which Gamache replies—to the shock of Croix—”It is an old and dangerous lie. It might be necessary, but it is never sweet and rarely right. It’s a tragedy.”

The quote is indeed Horace and originates in his Odes (111.2.13) and as Dr. Croix, the archeologist, points out, essentially means, “It is sweet and right to die for your country.” To which Gamache replies—to the shock of Croix—”It is an old and dangerous lie. It might be necessary, but it is never sweet and rarely right. It’s a tragedy.” The great World War I poet, Wilfred Owen, would borrow the phrase to title, arguably his most famous poem, Dulce et Decorum est, in which he describes the horrors of being gassed in the trenches on the Western Front.

The great World War I poet, Wilfred Owen, would borrow the phrase to title, arguably his most famous poem, Dulce et Decorum est, in which he describes the horrors of being gassed in the trenches on the Western Front.

Here she is with her Javanese monkey, Woo, who plays an important part in Louise’s book. And as Superintendent Therese Brunel points out, “She adored all animals, but Woo above all.”

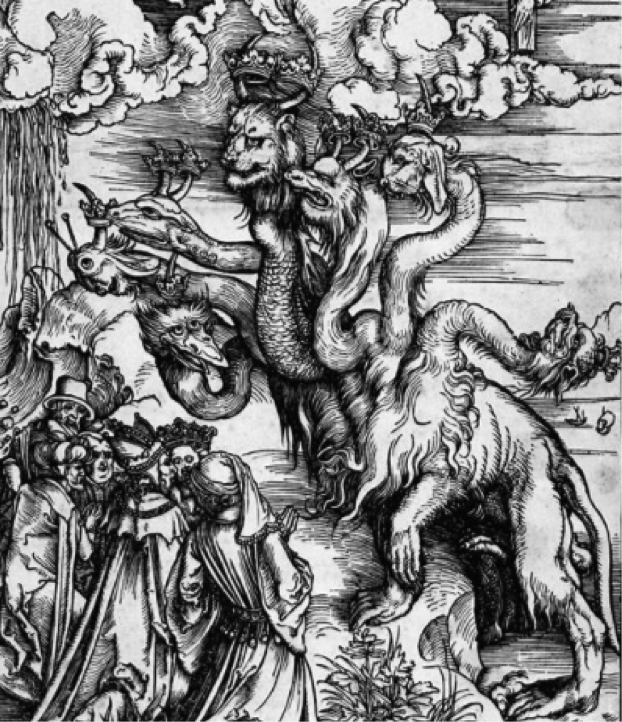

Here she is with her Javanese monkey, Woo, who plays an important part in Louise’s book. And as Superintendent Therese Brunel points out, “She adored all animals, but Woo above all.” The similarities between the real life Carr and Louise’s Clara are apparent. Both, of course, are painters and in a scene late in the novel, Superintendent Brunel and Clara sit before a statue of Carr where Therese tells Clara, “She looks a bit like you”. This is also the point in the book in which Brunel—while examining Clara’s painting —exclaims, “The Fall. My God, you’ve painted the Fall. That moment. She’s not even aware of it, is she? Not really, but she sees something, a hint of the horror to come. The Fall from Grace.”

The similarities between the real life Carr and Louise’s Clara are apparent. Both, of course, are painters and in a scene late in the novel, Superintendent Brunel and Clara sit before a statue of Carr where Therese tells Clara, “She looks a bit like you”. This is also the point in the book in which Brunel—while examining Clara’s painting —exclaims, “The Fall. My God, you’ve painted the Fall. That moment. She’s not even aware of it, is she? Not really, but she sees something, a hint of the horror to come. The Fall from Grace.”

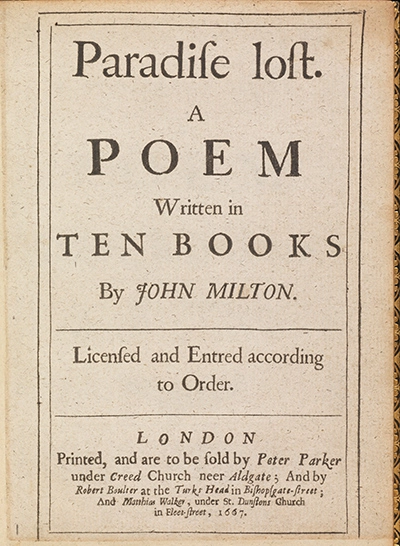

Echoed from John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, the quote above appears numerous times throughout Louise’s fourth book and serves as the defining mantra of the work.

Echoed from John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, the quote above appears numerous times throughout Louise’s fourth book and serves as the defining mantra of the work. Which brings us to the quote itself:

Which brings us to the quote itself:

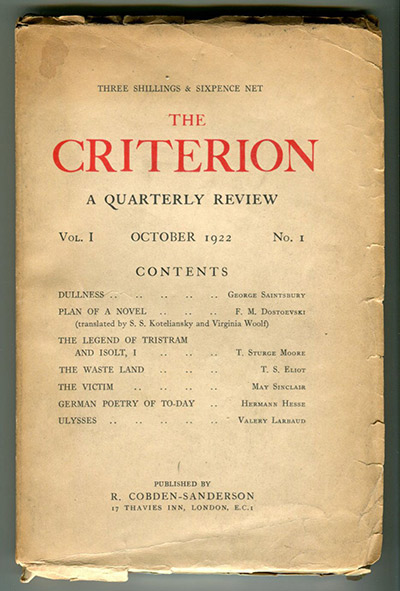

Originally published in The Criterion in 1922, The Waste Land was conceived by Eliot during what has come to have been described as a nervous breakdown and was heavily influenced by many things, including the Grail Legend, the work of James Joyce, Homer, and Hermann Hesse. The poem defines the prevailing desperation of the post-World War I generation as well as Eliot’s own tortured time.

Originally published in The Criterion in 1922, The Waste Land was conceived by Eliot during what has come to have been described as a nervous breakdown and was heavily influenced by many things, including the Grail Legend, the work of James Joyce, Homer, and Hermann Hesse. The poem defines the prevailing desperation of the post-World War I generation as well as Eliot’s own tortured time. Louise, as always, has chosen the perfect title because at the very core of this magnificent novel is the notion of rebirth and as the Gamache quote (at the top of page)—and Eliot’s own “April is the cruelest month” line—so profoundly illustrate is that rebirth can be accompanied by astonishing pain, even death.

Louise, as always, has chosen the perfect title because at the very core of this magnificent novel is the notion of rebirth and as the Gamache quote (at the top of page)—and Eliot’s own “April is the cruelest month” line—so profoundly illustrate is that rebirth can be accompanied by astonishing pain, even death.