wcag heading

“The mind is its own place, monsieur,” said Reine-Marie. “Can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.” (A Rule Against Murder)

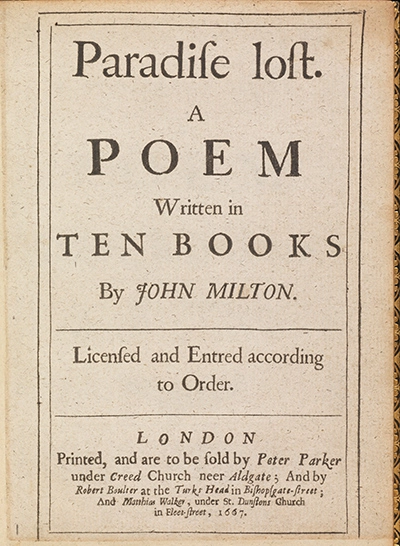

Echoed from John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, the quote above appears numerous times throughout Louise’s fourth book and serves as the defining mantra of the work.

Echoed from John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, the quote above appears numerous times throughout Louise’s fourth book and serves as the defining mantra of the work.

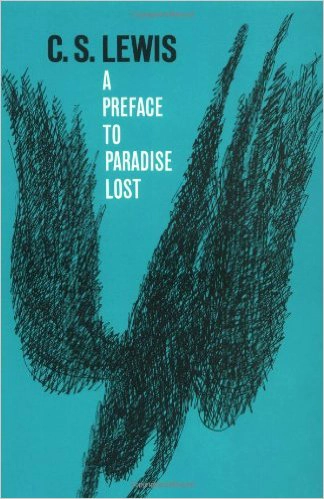

Originally published in 1667, Milton’s masterpiece has been interpreted in many ways—a scathing rebuke of corruption in the Anglican Church, a critical view of the Monarchy, a warning tome on civil war, and, as C.S. Lewis saw it, a straightforward morality tale. For those of you who have read our entry on Still Life, you know how big C.S. Lewis looms in Louise’s life and work. Professor Lewis was also quite the Milton scholar. He lectured extensively on the make-up and merits of Paradise Lost and wrote a singular thesis on the poem, A Preface to Paradise Lost, which was first published in 1942.

The Oxford Dictionary defines a morality tale as “a story or narrative from which one can derive a moral about right and wrong” and when boiled down A Rule Against Murder is just that: a choice between good or bad and how those decisions may lead to ruin. Or as Gamache observes, “To have it all and lose it. That’s what this case was about.”

Which brings us to the quote itself:

Which brings us to the quote itself:

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.

Satan, himself, speaks these words in Paradise Lost in an attempt to come to terms with his lost war with God and his banishment to the netherworld. Essentially he’s saying he can deal with Hell if he imagines it’s heaven.

In A Rule Against Murder, the Milton quote is rephrased no less than five times and as Louise explains, “life is perception. We make our own Heaven and Hell, depending on how we choose to view a situation. A huge success isn’t big enough, so we turn it into a disappointment. A loving relationship isn’t perfect, so we leave. A gift isn’t up to expectations, so instead of being happy, we are angry. We turn on the very people who are there to help us. In not recognizing Paradise, we lose it.”

But in this book, Louise also deftly turns Satan’s statement on its head and uses it as a beacon of hope. There doesn’t have to be a hell at all. If we choose the path of goodness, to paraphrase Reine-Marie, “there will always be a heaven.”

Brilliant!

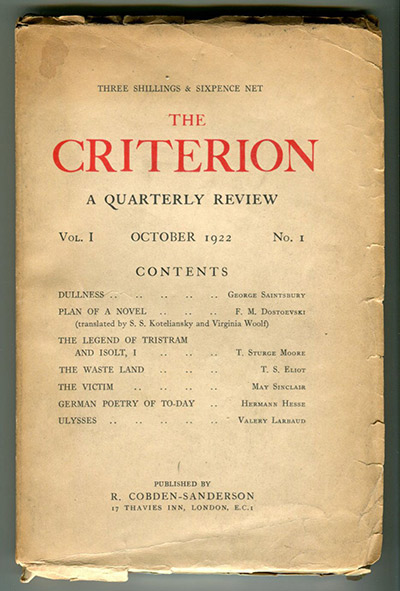

Originally published in The Criterion in 1922, The Waste Land was conceived by Eliot during what has come to have been described as a nervous breakdown and was heavily influenced by many things, including the Grail Legend, the work of James Joyce, Homer, and Hermann Hesse. The poem defines the prevailing desperation of the post-World War I generation as well as Eliot’s own tortured time.

Originally published in The Criterion in 1922, The Waste Land was conceived by Eliot during what has come to have been described as a nervous breakdown and was heavily influenced by many things, including the Grail Legend, the work of James Joyce, Homer, and Hermann Hesse. The poem defines the prevailing desperation of the post-World War I generation as well as Eliot’s own tortured time. Louise, as always, has chosen the perfect title because at the very core of this magnificent novel is the notion of rebirth and as the Gamache quote (at the top of page)—and Eliot’s own “April is the cruelest month” line—so profoundly illustrate is that rebirth can be accompanied by astonishing pain, even death.

Louise, as always, has chosen the perfect title because at the very core of this magnificent novel is the notion of rebirth and as the Gamache quote (at the top of page)—and Eliot’s own “April is the cruelest month” line—so profoundly illustrate is that rebirth can be accompanied by astonishing pain, even death.