wcag heading

Gamache took the bread to the long pine table, set for dinner, then returned to the living room. He reflected on T.S. Eliot and thought the poet had called April the cruelest month not because it killed flowers and buds on the trees, but because sometimes it didn’t. How difficult it was for those who didn’t bloom when all about was new life and hope. (The Cruelest Month, page 248, Trade Paperback Edition)

How serendipitous to offer this post up in the month of April when the novel itself is set and the month—by way of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land—that has provided one of the most recognizable lines in modernist poetry.

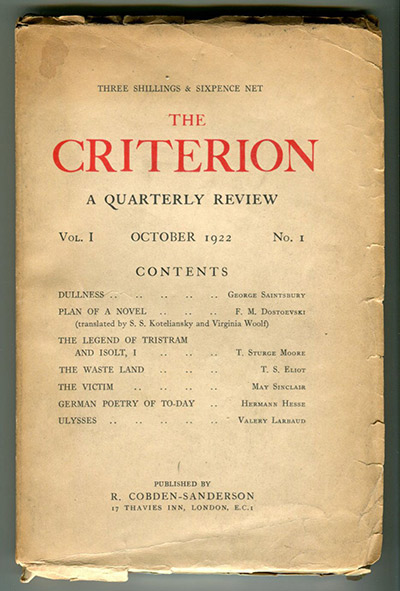

Originally published in The Criterion in 1922, The Waste Land was conceived by Eliot during what has come to have been described as a nervous breakdown and was heavily influenced by many things, including the Grail Legend, the work of James Joyce, Homer, and Hermann Hesse. The poem defines the prevailing desperation of the post-World War I generation as well as Eliot’s own tortured time.

Originally published in The Criterion in 1922, The Waste Land was conceived by Eliot during what has come to have been described as a nervous breakdown and was heavily influenced by many things, including the Grail Legend, the work of James Joyce, Homer, and Hermann Hesse. The poem defines the prevailing desperation of the post-World War I generation as well as Eliot’s own tortured time.

Eliot described his epic poem as, “the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life . . . just a piece of rhythmical grumbling.” Despite the poet’s own downplaying of his work, a vast number of significant critics disagreed with him. Conrad Aiken called it, “One of the most moving and original poems of our time” while Ezra Pound— who had a heavy hand in editing Eliot’s masterpiece—called it a “justification” of “our modern experiment”.

At its heart, The Waste Land is about rebirth—the revitalization of society after the catastrophes of war, the restoration of the mind after the ravages of mental illness, and the reinvigoration of the spirit after prolonged dejection.

Louise, as always, has chosen the perfect title because at the very core of this magnificent novel is the notion of rebirth and as the Gamache quote (at the top of page)—and Eliot’s own “April is the cruelest month” line—so profoundly illustrate is that rebirth can be accompanied by astonishing pain, even death.

Louise, as always, has chosen the perfect title because at the very core of this magnificent novel is the notion of rebirth and as the Gamache quote (at the top of page)—and Eliot’s own “April is the cruelest month” line—so profoundly illustrate is that rebirth can be accompanied by astonishing pain, even death.

We witness this throughout the book from the reoccurring theme of Easter (the death and rebirth of Christ), the rebirth of flora and fauna when winter turns to spring, Ruth and the ducklings Rosa and Lillium, to the séance itself (the living communicating with the dead).

In closing, I can’t help but point out one of the great “wink and nods” from the novel that concretely connects T.S. Eliot to Louise’s tome and that is Jeanne Chauvet using the nom de plume “Madame Blavatsky”.

The real Blavatsky, an infamous occultist of the late 19th Century, was heavily referenced in Eliot’s 1919 poem, The Cooking Egg:

Madame Blavatsky will instruct me

And, like Blavatsky, Chauvet offers her own guidance throughout The Cruelest Month.